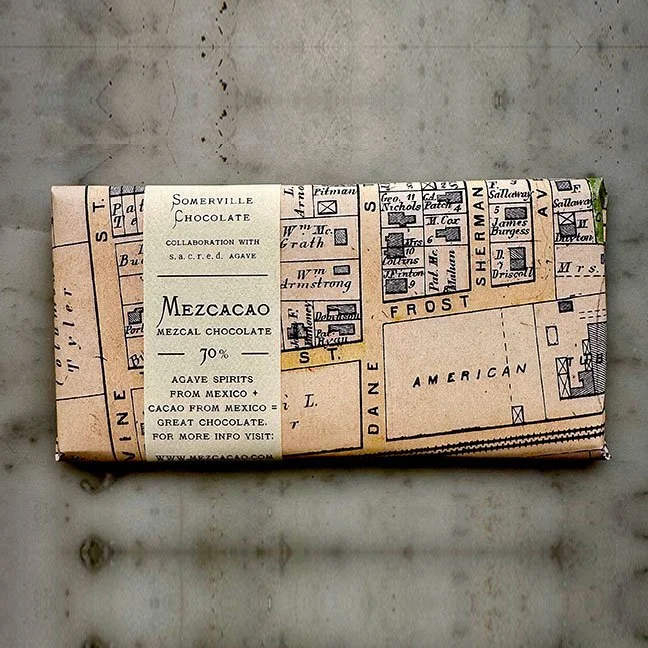

MezCacao

You got your Mezcal in my chocolate…?

Basically, this chocolate bar is the result of two people (Eric Parkes at Somerville Chocolate and Lou Bank at SACRED) who each love craft chocolate and craft Mexican spirits hanging out one afternoon eating craft chocolate and drinking craft Mexican spirits and talking about how they both liked eating craft chocolate and drinking craft Mexican spirits and wouldn’t it be fun to do something together that involved craft chocolate and craft Mexican spirits.

But also, this chocolate bar is about biodiversity. And small farmers. And Mexico.

When you drink Mezcal — if you drink Mezcal — nine times out of ten you are drinking one variety of one species of agave. You’re drinking Espadin. And you’re drinking Espadin Mezcal from one place: Oaxaca. But at least 24 of Mexico’s 31 states have a history of making spirits with agave. And there are 158 recognized species of agave — and multiple varieties of each of those species. But you’re really only drinking … well, truthfully, you’re really only drinking Blue Weber agave, converted into Tequila in the state of Jalisco. And that’s created a monoculture in that state that is putting the biodiversity of that region at risk. But when you think you’ve expanded beyond Tequila and Blue Weber by drinking Mezcal, really, you’ve just started creating another monoculture in another state.

Meanwhile, over in the state of Puebla, our friend Ildefonso Macedas Ginez is using agaves like Papalometl (a variety of agave Potatorum) to make spirits. He’ll call it mezcal, but — longer story for another time — he can’t use that word in commerce since the Mexican government stole the word Mezcal from the people. But over there in San Luis Atolotitlan, Puebla, Ildefonso is cooking a number of different agaves underground in a stone-lined earthen oven; milling them by hand using wooden hammers; fermenting that cooked agave in plastic barrels; then distilling that fermented agave first in a wood-fired steel still and then refining it in a wood-fired copper still.

So … we took two liters of that Papalometl agave spirit by Ildefonso and set aside. Then we contacted our friend Monica Garcia Teruel at Origen Tierra, who also likes craft chocolate and craft Mexican spirits, and we asked her to find us a Mexican cacao that reflects the beautiful biodiversity of that plant. She came back with an ensamble of varieties, including amelonados, acriollados, and some hybrids, all sourced from dozens of farmers in La Chontalpa community of Tabasco (no relation to the hot sauce).

In the same way that we’re creating agave monocultures by only drinking spirits made from one (and a little bit of a second) agave, we’re really only eating chocolate made from one cacao: Forastero. And mainly from Africa. But there are about a dozen different varieties of cacao. I say “about” because genetics with cacao can get confusing — a single pod from a specific tree can contain seeds (or “beans”) from multiple varieties of cacao. But the genetics of that mother tree are important — maintaining healthy populations of multiple genetic varieties of cacao can ensure that the plant (and our access to chocolate) is resilient to pestilence, disease, and climate change.

This beautiful, genetically diverse mix of cacaoas arrived to Somerville Chocolate, where it was roasted, bathed in Ildefonso’s Papalometl spirit, dried, and then refined into these chocolate bars. These delicious bars are more biologically and genetically diverse than the bars one would normally eat. They also combine a complex set of flavors from two very different foods, each with a long tradition of refinement.

Every time we consume something, we are making a choice, consciously or subconsciously. Choose something that honors genetic diversity, draws upon its rich tradtion as a food or drink, and lets you experience a downright delicious set of flavors. Both you and the world will be better off for it.